Cats get heartworm infections!

Just like dogs, cats get infected with heartworms. But in felines, the disease presents a little differently and is much harder to detect. Sometimes the first symptoms are respiratory issues and death!

Feline heartworm disease tends to be more of a lung disease rather than a heart disease as it is in dogs. The parasite is the same but because the heartworm’s natural host is not a cat, the interaction between worm and host creates a very different condition. It isn’t good for either the cat nor is it good for the worm.

Inside the cat – what happens:

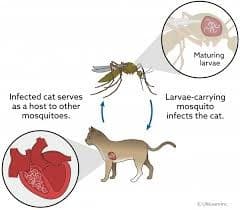

The story begins with a mosquito. The mosquito feeds on a heartworm infected dog, the heartworm microfilaria (the youngest larvae) are sipped up into the mosquito during feeding, and develop in the mosquito’s body for the next couple of weeks. This is all according to plan for the heartworm’s life cycle until the mosquito bites a cat instead of another dog.

The third stage larval heartworms enter the cat’s body and develop in the tissues. The feline body is an inhospitable host and worm development is fraught with immunological attack. By the time the larva has reached its 5th stage, it is on its way to the pulmonary arteries to complete its maturation but most infections will end here as the feline immune system is nearly relentless in its assault. Only about 25 percent of the original infecting larvae will survive to adulthood, which means most infections are aborted in this last stage of larval development.

Most cats with adult heartworms only have a few worms (1-3 on average) and development to the adult stage takes an extra couple of months in the feline body compared to the canine body. Often, there is a single sex worm population, so reproduction is unlikely. Only about 20% of feline infections produce microfilaria (baby worm larvae); further, the feline immune system is so aggressive that the larvae only live a matter of weeks whereas they can live for up to 2 years in a dog.

In cats, when the adult heartworm eventually dies, a huge amount of inflammation is generated and many cats do not survive this stage. If the cat does survive, there is likely long-term damage to the lung tissue.

It is unclear what percentage of an area’s feline population will be infected. The standard statistic is that a region’s feline incidence will be approximately 10% of the canine incidence but this appears to be a low estimation since feline infection cannot be detected by the presence of adult worms.

- Cats living in heartworm areas should be given heartworm prevention medications just as dogs should.

- In one study, 25-30% of heartworm infected cats were described as being indoor cats. Mosquitos are not shy about entering homes

Heartworm disease in cats can produce an assortment of clinical pictures. In cats, heartworm disease is more frequently a lung disease and not a vascular disease as i dogs. It is the baby worms along with dying adult heartworms that cause all the trouble in feline heartworm disease. And in either instance, the end result is severe.

- Coughing, wheezing, difficulty breathing.

- Vomiting

- Disease related to embolism or abnormal clots.

- Extreme nosebleed.

- Neurologic signs (probably associated with larvae accidentally migrating to the brain.)

- 10-20% of cats experience sudden death. (This is probably associated with death of adult worms.)

- Many cats never show noticeable symptoms and most of these cats (80% approximately) clear the infection on their own. How many cats are infected without symptoms? The answer is not clear because it is the symptomatic cats that get the most medical scrutiny.

Heartworm-Associated Respiratory Disease, or “HARD”

Also known as Pulmonary Larval Dirofilariasis

As stated, cats are not a natural host for the heartworm, which means the migrating larval heartworms are not likely to complete their life cycle. To recap from above, baby heartworms called microfilaria are slurped up by the mosquito feeding on an infected dog. The slurped up young heartworms must spend enough time (several weeks) in the mosquito’s body to develop into an infective stage at which point it is ready to infect a new host. The infective stage heartworm larva is deposited in a drop of mosquito spit adjacent to a mosquito bite, the larvae crawl into the skin puncture made by the mosquito, gain access to their new host, and continue to develop in the soft tissues of the new host, eventually making their way into the circulation and to the host’s pulmonary arteries.

The migrating young worm uses molecular signposts to tell it how to get to its host’s pulmonary arteries where it wants to finish growing up, mate and live out its life. The worm is prepared to read CANINE signposts and does not always migrate correctly trying to understand feline protein signals. The worm may get lost and end up who knows where in the body. If the young worms get to the pulmonary arteries at all, most of them are killed by the especially reactive feline immune response against them.

It is this immune reaction that causes heartworm disease in cats and it can start as soon as 75-90 days after the infecting mosquito bite.

When young heartworms die in the pulmonary arteries, the immune system breaks them into fragments and attempts to remove them. The resulting inflammation leads to lung disease which manifests as coughing, respiratory effort, and vomiting. The inflammation associated with the death of fifth stage heartworm larvae is vastly compounded should a coexisting adult heartworm die. In this situation, yet more inflammation results and even if the cat survives, all this inflammation creates permanent damage in the delicate lung tissues.

HARD mimics feline asthma and the two diseases look identical on radiographs. Cats with HARD will cough, wheeze (a musical respiratory sign similar to a sigh), and vomit (though it may be hard to tell aggressive productive coughing from vomiting). Breathing may be shallow and rapid and may progress to actual respiratory distress. Heartworm testing is the only way to distinguish these conditions.

While in most situations feline heartworm disease is a lung disease and not a vascular disease as it is in dogs, sometimes cats do get adult worms in their pulmonary arteries just as dogs do. These adult worms do not live as long as they do in the canine body and they do not achieve the same length/size. If they find a mate and give birth to microfilariae, the microfilariae are promptly killed by the feline immune system within the first month. In short, in the feline pulmonary artery, heartworms are much smaller. You would think this would make for milder vascular disease, but because cats are so small even one adult worm takes up a great deal of space in the vasculature.

The more usual lung disease is all the worse if the reaction against the immature worms is complicated by a surviving adult worm in the vasculature. When this parasite finally dies, the subsequent blood clots and inflammation is frequently fatal to cats.Vascular Disease is Separate from HARD

Most of heartworm disease in cats is caused by the inflammatory reaction generated by the worm. In dogs, heartworm disease is mostly about the obstruction of blood flow from the physical size of the worms.

Symptoms of Disease

The cat’s immune system is extremely reactive against heartworms. For this reason, it is virtually impossible to detect microfilariae in an infected cat. (The cat’s immune system removes them too quickly.) Also, symptoms of infection tend to be more immune-related than heart-failure related. Cats develop more of a lung disease, complete with respiratory distress, and chronic coughing or vomiting. Feline heartworm disease is often misdiagnosed as feline asthma. Sudden death may occur just as it may occur in infected dogs.

In cats there are two phases where the disease can exert symptoms. The first is when immature worms reach the lung and pulmonary arteries, as early as 75 to 90 days after infection. Even small worms are inflammatory and disruptive to the circulation. Cells of inflammation infiltrate the lung and interfere with the cat’s ability to breathe. The second phase where problems can occur is when the worm dies. Since cats are not the natural host for this parasite, most immature worms that make it to the lung are killed. The presence of the dead worm is extremely inflammatory. (Imagine your body trying to remove or digest the dead body of another animal inside your lung and circulation!)

The effects of this kind of widespread inflammation can reach far beyond the lung and circulatory system. The kidney can be affected as well as the gastrointestinal tract and even the nervous system.

Diagnostic Testing

Antigen Testing

In dogs, diagnosis is usually not complicated. A blood sample is tested for proteins that can only be found on the skin of the adult female heartworm. Most dogs have a population of worms in their arteries, so even one female worm will cause an antigen test to show positive. In cats, disease is caused by immature worms, not adult worms female or otherwise, so this kind of testing has limited applications. There may be no adult worms at all to generate a positive antigen test, yet the cat is infected.

Antibody Testing

Antibody testing may be more sensitive but is not adequate alone. A negative antibody test is good evidence that the cat is not infected; however, a positive antibody test may indicate several things. It could indicate a mature infection with one or more adult worms, immature worms in the body, or a past infection. (Antibody levels will remain somewhat elevated after the heartworms have long since died.)

So if no single test is reliable, what are we supposed to do for testing? First of all, unlike dogs where annual screening is the norm, healthy cat screening is probably not necessary. Instead, testing is best done if a cat is sick and heartworm disease is suspected. There is still some controversy about what testing should be accomplished in a symptomatic cat. Both antibody and antigen tests in combination are recommended by some experts, while others feel the antibody test alone is probably adequate. Of course, a cat with respiratory disease probably should have chest radiographs and cardiac echocardiography to further define the condition at hand.

Microfilaria Testing

In dogs, testing for microfilariae (offspring of adult heartworms born in the host’s body) are also commonly performed. Unfortunately, in cats microfilaria testing is virtually worthless. First, infected cats usually do not have enough adult worms for the production of offspring. There may be only a few adult worms; single sex infection is common. Further, microfilariae, if any, are simply cleared too quickly by the host’s immune system and are rarely detected. As mentioned, in cats heartworm disease stems at least in part from migrating immature larvae. No adult worms (and thus no off-spring) are necessary for disease so microfilariae testing is not worthwhile in cats.

Treatment

Since the major signs of disease in the cat are due to inflammation and immune stimulation, a medication such as prednisolone can be used to control symptoms. A bacteria called Wolbachia commonly lives within the heartworm and enhances its ability to generate inflammation. A course of doxycycline is often recommended to address these bacteria. The doxycycline course is short but the prednisolone will be long term. If the cat does not appear sick, the American Heartworm Society recommends attempting to wait out the adult worm’s 2-3 year life span and simply monitor chest radiographs every 6 months or so. Median survival time is 1.5 years for heartworm infection in cats. Radiographs are monitored to check progress.

One might wonder why we cannot use the same treatment as we do for dogs to kill any adult heartworms a cat might have. Actually, the same heartworm adulticide therapy used in dogs is best not used in cats as it is extremely dangerous to do so and is considered a last resort. There may not be a choice, however, depending on the degree of illness from the heartworm disease. Approximately one third of cats receiving heartworm adulticide therapy will experience life-threatening embolic complications when the worms die suddenly (generally an unacceptable statistic). One month of cage confinement is typically recommended to control circulatory effort after adulticide treatment and adulticide therapy should be consider the last resort for an infected cat where symptoms of the disease cannot be controlled with prednisone.

Prevention

In studies of infected cats, 25% of infected cats were considered indoor only cats. Because of this and the disastrous effect of even one heartworm to a cat, the American Heartworm Society recommends monthly prevention for all cats living in heartworm endemic areas.

There are products on the market that are reliably effective:

Heartgard was the first FDA-approved heartworm prevention medication available for cats. It is a monthly flavored chewable available by prescription. The American Heartworm Society recommends testing prior to administration.

Interceptor® also makes a monthly chewable for cats with the same active ingredient (milbemycin oxime) as Interceptor for dogs. Interceptor for cats also protects against hookworms and roundworms.

Revolution® entered the anti-parasite scene in 1999. This product covers fleas, roundworms, hookworms, and ear mites in addition to preventing heartworm in cats. This product is applied topically rather than orally.

Advantage Multi® combines imidocloprid for flea control and moxidectin for heartworm preventive in one product. This product is also applied topically.