The virus known as Parvovirus often seen in young, unvaccinated puppies originated from a cat virus that causes the feline infection Panleukopenia.

While the two viruses are variations of the same virus and can be infectious to either species and share some overlap, they do present slightly differently in cats versus dogs.

In general, parvoviruses are non-enveloped viruses (no fat / no lipid covered coating around it) that contain a single strand of DNA. The lack of the lipid envelope means the virus requires more than just soap and water, which can penetrate into fat, destroying its envelope and leaving the virus unprotected.

By not having a lipid envelope, parvoviruses requires other disinfectants to kill it.

But this article is less about the viruses structure and more about the disease it causes in cats and dogs, how to prevent it and if your pet has it, how to treat it.

Similarities:

Parvoviruses like to attack rapidly dividing cells, which explains its penchant for bone marrow and the intestinal tract. Cells here are being rapidly made all the time, so cell division is common.

Parvovirus infections in the dog are classic for symptoms initially to be gastrointestinal – vomiting, diarrhea and loss of appetite. In more severe infections, the bone marrow is affected and one can see a drop in the number of white blood cells found.

Infections in the cat often affect the bone marrow first but diarrhea, vomiting and decreased appetite can also occur. The disease in cats is called panleukopenia which refers to a drop in most of the white blood cells. It should also be noted that panleukopenia is a little more refractory to treatment and the mortality rate is higher.

In both species, a drop of the white cell lines requires broad spectrum antibiotic therapy and gastro-intestinal symptoms are treated with anti-emetics, appetite stimulants, fluid therapy to replenish losses from diarrhea and vomiting and in many cases assist feeding of a nasogasto feeding tube may need to be placed to trickle small amounts of food into the sick patient.

More mild cases (more referring to parvovirus) can be successful with diligent treatment by the owner on an out-patient basis) whereas more severe cases and usually panleukopenia require in-patient hospitalization and ongoing supportive care.

There is a simple in-house test that picks up most cases of canine parvovirus and panleukopenia virus. This coupled with the symptoms, vaccine history and labwork can help your veterinarian confirm the diagnosis.

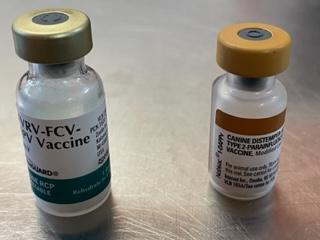

In both cats and dogs, vaccinations are available and should be started between six and eight weeks of age to prevent infection with this virus. puppies and kittens should be vaccinated with this vaccine every 2–4 weeks until between 18–20 weeks of age.

While they are being vaccinated and developing their immune system, puppies and kittens should be kept away from other dogs and cats and areas they inhabit as the virus is eliminated in fecal matter and can live for some time in the environment.

Vaccination is very effective in preventing the virus. It should be noted that puppies and kittens are more susceptible but any dog or cat, even if older, that has not been properly vaccinated and boostered, is also susceptible to contracting the virus.

So if you have a mature dog or cat that has never been vaccinated or has an unknown vaccine history, please talk to your veterinarian as they will likely need a 2-injecton vaccination series to develop initial immunity, followed in a year by a third booster