The Basics

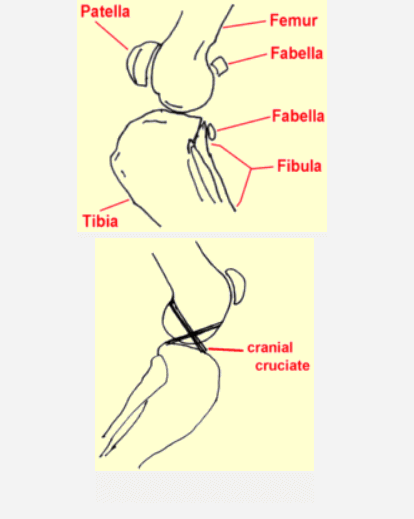

The knee is a fairly complicated joint. It consists of the femur above, the tibia below, the kneecap (patella) in front, and the bean-like fabellae behind. Chunks of cartilage called the medial and lateral menisci fit between the femur and tibia like cushions. An assortment of ligaments holds everything together, allowing the knee to bend the way it should and keep it from bending the way it shouldn’t.

There are two cruciate ligaments that cross inside the knee joint: the anterior (or, more correctly in animals, cranial) cruciate and the posterior (in animals, the caudal) cruciate. They connect from one side of the femur on top to the opposite side of the tibia on the bottom, the two ligaments forming an X (hence the name cruciate) inside the knee joint. They are named for their attachment site on the tibia (the cranial cruciate attaches to the front of the tibia and the caudal cruciate attaches to the back of the tibia). This may be hard to visualize based on the description but the illustration above shows the orientation of the two crossing ligaments effectively. The anterior/cranial cruciate ligament prevents the tibia from slipping forward out from under the femur.

The ruptured cruciate ligament is the most common knee injury of dogs; in fact, chances are that any dog with sudden rear leg lameness has a ruptured anterior cruciate ligament rather than something else. The history usually involves a rear leg suddenly so sore that the dog can hardly bear weight on it. If left alone, it will appear to improve over the course of a week or two but the knee will be notably swollen and arthritis will set in quickly. Dogs are often seen by the veterinarian in either the acute stage shortly after the injury or in the chronic stage weeks or months later.

Finding the Rupture

The key to the diagnosis of the ruptured cruciate ligament is the demonstration of an abnormal knee motion called a drawer sign. It is not possible for a normal knee to show this sign.

The Drawer Sign

Another method is the tibial compression test where the veterinarian stabilizes the femur with one hand and flexes the ankle with the other hand. If the ligament is ruptured, again the tibia moves abnormally forward.The veterinarian stabilizes the position of the femur with one hand and manipulates the tibia with the other hand. If the tibia moves forward (like a drawer being opened), the cruciate ligament is ruptured.

If the rupture occurred some time ago, there will be swelling on side of the knee joint that faces the other leg. This is called a medial buttress and is a sign that arthritis is well along.

It is not unusual for animals to be tense or frightened at the vet’s office. Tense muscles can temporarily stabilize the knee, preventing demonstration of the drawer sign during examination. Often sedation is needed to get a good evaluation of the knee. This is especially true with larger dogs. Eliciting a drawer sign can be difficult if the ligament is only partially ruptured so a second opinion, X-rays or consult with an orthopedic surgeon may be needed if the initial examination is inconclusive.

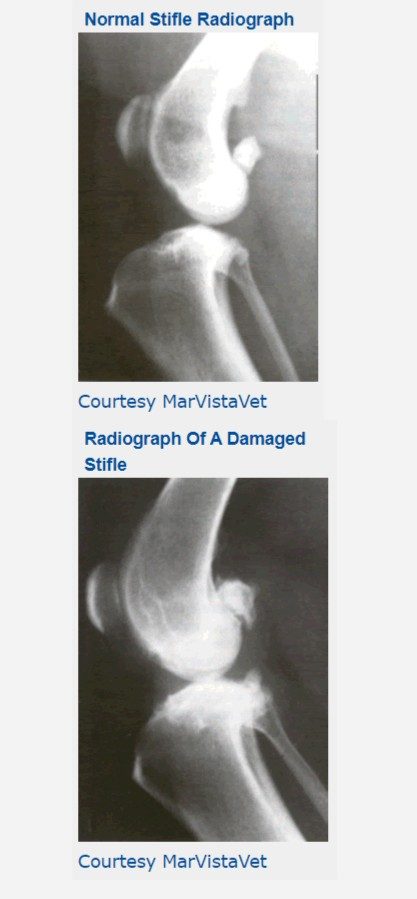

Since arthritis can set in relatively quickly after a cruciate ligament rupture, radiographs (x-rays) to assess arthritis are helpful. Another reason for radiographs is that occasionally when the cruciate ligament tears, a piece of bone where the ligament attaches to the tibia breaks off as well. This will require surgical repair and the surgeon will need to know about it before beginning surgery.

How Rupture Happens

Several clinical pictures are seen with ruptured cruciate ligaments. One is a young athletic dog playing roughly who takes a bad step and injures the knee. This is usually a sudden lameness in a young large-breed dog.

A recent study identified the following breeds as being particularly at risk for this phenomenon: Labrador retriever, Golden retriever, Rottweiler,Neapolitan mastiff, Newfoundland, Akita, St. Bernard, Rottweiler, Chesapeake Bay retriever, and American Staffordshire terrier.

On the other hand, an older large dog, especially if overweight, can have weakened ligaments and slowly stretch or partially tear them. The partial rupture may be detected or the problem may not become apparent until the ligament breaks completely. In this type of patient, stepping down off the bed or a small jump can be all it takes to break the ligament. The lameness may be acute but have features of more chronic joint disease or the lameness may simply be a more gradual/chronic problem.

Larger, overweight dogs that rupture one cruciate ligament frequently rupture the other one within a year’s time.

An owner should be prepared for another surgery in this time frame.

Cruciate rupture is not limited to large breed dogs. Small dogs can rupture their ligaments as well and, while arthritis is slower to set in when the patient is not as heavy, there is an association with cruciate rupture and medial luxating patella that is very common in small breed dogs. With the patellar luxation, the kneecap flips in and out of the patellar groove. If the condition is relatively mild, it may not require surgical correction but it does stress the cranial cruciate ligament and can predispose to rupture.Normal Stifle Radiograph

What Happens if the Cruciate Rupture is Not Surgically Repaired

Without an intact cruciate ligament, the knee is unstable. Wear between the bones and meniscal cartilage becomes abnormal and the joint begins to develop degenerative changes. Bone spurs called osteophytes develop resulting in chronic pain and loss of joint motion. This process can be arrested or slowed by surgery but cannot be reversed.

- Osteophytes are evident as soon as 1 to 3 weeks after the rupture in some patients. This kind of joint disease is substantially more difficult for a large breed dog to bear, though all dogs will ultimately show degenerative changes. Typically, after several weeks from the time of the acute injury, the dog may appear to get better but is not likely to become permanently normal.

- In one study, a group of dogs was studied for 6 months after cruciate rupture. At the end of 6 months, 85% of dogs less than 30 pounds of body weight had regained near normal or improved function while only 19% of dogs over 30 pounds had regained near normal function. Both groups of dogs required at least 4 months to show maximum improvement.

What Happens in Surgical Repair?

There are three different surgical repair techniques commonly used today. Every surgeon will have their own preference for which technique is best for a given patient’s situation.

Extracapsular Repair

This procedure represents the traditional surgical repair for the cruciate rupture. It can be performed without specialized equipment and is far less invasive than the newer procedures described below. First, the knee joint is opened and inspected. The torn or partly torn cruciate ligament is removed. Any bone spurs of significant size are bitten away with an instrument called a rongeur. If the meniscus is torn, the damaged portion is removed. A large, strong suture is passed around the fabella behind the knee and through a hole drilled in the front of the tibia. This tightens the joint to prevent the drawer motion, effectively taking over the job of the cruciate ligament.

- Typically, the dog may carry the leg up for a good two weeks after surgery but will increase knee use over the next 2 months eventually returning to normal.

- Typically, the dog will require 8 to 12 weeks of exercise restriction after surgery (no running, outside on a leash only including the backyard.

- The suture placed will break 2 to 12 months after surgery and the dog’s own healed tissue will hold the knee.

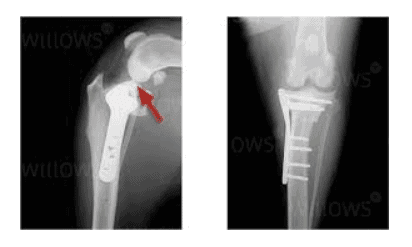

Tibial Plateau Leveling Osteotomy (TPLO)

This procedure uses a fresh approach to the biomechanics of the knee joint and was developed with larger breed dogs in mind. The idea is to change the angle at which the femur bears weight on the flat “plateau” of the tibia. The tibia is cut and rotated in such a way that the natural weight-bearing of the dog actually stabilizes the knee joint. As before the knee joint still must be opened and damaged meniscus removed. The cruciate ligament remnants may or may not be removed depending on the degree of damage.

This surgery is complex and involves special training in this specific technique. Many radiographs are necessary to calculate the angle of the osteotomy (the cut in the tibia). This procedure typically costs substantially more than the extracapsular repair as it is more invasive to the joint.

- Typically, most dogs are touching their toes to the ground by 10 days after surgery although it can take up to 3 weeks.

- As with other techniques, 8-12 weeks of exercise restriction are needed.

- Full function is generally achieved 3 to 4 months after surgery and the dog may return to normal activity.

Which Procedure is Better?

The TPLO is more invasive and requires special equipment and advanced orthopedic surgical training to perform. During recovery, it has more potential for complication. However, especially for larger dogs, it is generally considered to be the preferred method of correction. While a decade ago TPLOs were relatively new and complications higher, today, most boarded veterinary surgeons do many of these procedures weekly and they have become very routine.

Also, there is some evidence that recovery to normal function may be faster with the newer procedures. Controversy continues and there are strong opinions favoring each of the three procedures. Discuss options with your veterinarian in order to decide.

General Rehabilitation after Surgery

Rehabilitation following either repair requires about 8 weeks of strict exercise restriction. Over the first two weeks light exercise can increase and continue to increase until full recovery from surgery. Passive range of motion exercise where the knee is gently flexed and extended can also help.After the stitches or staples are out (or after the skin has healed in about 10 to 14 days), water treadmill exercise can be used if a rehabilitation facility is available and if you elect to undertake true physical therapy.