High blood pressure is an extremely important concern in human medicine. But what about our pets? They don’t smoke or worry about the mortgage and they don’t deposit cholesterol in their blood vessels.

They do, however, get high blood pressure, especially related to diseases that coincide with advancing age. The information below is designed to help give you a better understanding.

What happens with High Blood Pressure?

Problems from high blood pressure arise when a blood vessel is simply too small for the high pressure flow going through it. Smaller vessels can hemorrhage from being under high pressure. The smaller vessels are more prone to this happening and due to being small, the bleeding may not be noticeable but blood vessel destruction can create problems over time.

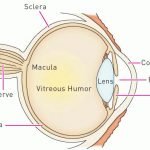

The retina of the eye is especially at risk, with either sudden or gradual blindness often being the first sign of latent high blood pressure. The kidney also is a target as it relies on tiny vessels to filter toxins from the bloodstream. That said, kidney disease is also a major cause of high blood pressure and also progresses far more rapidly with it.

High blood pressure also increases the risk of embolism: the formation of tiny blood clots that form when blood flow is abnormal. These clots can lodge in an assortment of inopportune locations including the brain, leading to strokes or mini-strokes.

What Causes High Blood Pressure in Pets?

There are numerous diseases in pets that are associated with high blood pressure:

- Chronic renal (kidney) failure In one study, 93% of dogs with chronic renal failure and 61% of cats with chronic renal failure also had systemic hypertension.

- Hyperthyroidism In one study, 87% of cats with untreated hyperthyroidism had systemic hypertension. (hyperthyroidism is a cat disease.)

- Glomerular disease is one of the kidney filtration system in which protein is lost in urine. It is important to screen pets with high blood pressure for urinary protein as control of protein loss is important to survival time.

- Cushing’s disease (more common in dogs but occasionally seen in cats

- Diabetes mellitus (inability to properly reduce blood sugar)

- Pheochromocytoma (an adrenaline secreting tumor of the adrenal gland)

- Other causes

While in people, high blood pressure is usually considered primary, meaning there is no underlying disease causing it, in animals, there is almost always another disease causing it and if routine screening does not identify the problem, more tests may be in order.

How is High Blood Pressure Identified?

We can measure blood pressure in pets just the way we do in people and we have more reason to do so if there is a known underlying disease that predisposes to hypertension. It has recently been recommended that older pets have their blood pressure checked whenever they have a physical examination.

There is some disagreement among experts as to which patients should be screened. Ask your veterinarian if your senior pet should get a blood pressure measurement.

The other time high blood pressure is discovered is when it makes its presence known. This usually means some degree of blindness or some other obvious eye problem. Also in animals that suddenly become weak of have symptoms suggestive of a stroke such as a neurological change – head tilt, unsteady walk, etc.

Do not let minor vision changes go unreported. Let your veterinarian know if you think your pet’s vision is not normal.

Retinal changes can be complicated to interpret. Do not be surprised or alarmed if your veterinarian recommends referral to a veterinary ophthalmologist.

How do we Measure Blood Pressure in Pets?

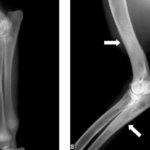

Blood pressure measurement is performed similarly to the way it is in humans. An inflatable cuff is fit snuggly around the foot, foreleg, or even tail of the pet. The cuff is inflated so as to occlude blood flow through the superficial artery. In a person, as the cuff is slowly deflated, a stethoscope is used to listen for the point when the blood pressure is adequate to pump through the partially occluded vessel. This point on the pressure gauge is the systolic blood pressure.

In pets, this measurement should not exceed 150. Treatment should be initiated at readings of 160 or greater. A reading of 180 is considered by the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine to indicate high risk for organ damage while readings of 150-159 are considered mildly elevated.

Some pets (obviously) are nervous at the vet’s office and this factor must be taken into account when reading blood pressure. It is possible for a pet to have high blood pressure at the vet’s office and normal pressure at all other times.

What Treatment is Available for Hypertension?

Ocular disease may require prescription eye drops depending on how much bleeding is in the eye and whether or not return of vision is likely.

When hypertension is identified, a search for the underlying cause is indicated. It may be that controlling the underlying disease totally reverses the hypertension (especially true for hyperthyroid cats).

Beyond these methods, as with people, medication to lower blood pressure is often in order. This typically involves some type of pill that dilates peripheral blood vessels, effectively making them larger so as to accommodate the high pressure blood flow going through them.

Amlodipine is a calcium channel blocker that dilates the systemic arterioles. It is the most effective drug for treating feline hypertension, with the fewest side-effects. The drug is also effective in dogs, but literature documentation is lacking. Amlodipine in dogs has always been expensive, but recently a generic version of the drug has become available, which should make it more cost effective.

Amlodipine can also be applied transdermally, although the clinical effect may be less than with orally administered amlodipine.

Similar to people Angiotensin-Receptor Blockers (ARBs) can be very effective at lowering systemic blood pressure and are gaining traction in veterinary medicine.