While dogs and cats typically don’t smoke, eat salty foods and have the same type of stresses humans do, they can still come down with a number of conditions that lead to high blood pressure. Just as in humans, high blood pressure is an extremely important concern. Most of people know or have heard how serious it can be. The information below reviews the basics on hypertension in companion animals.

What does High Blood Pressure Do?

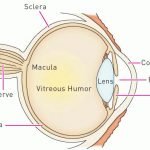

Small vessel bleeds are one result of elevated blood pressure. While it starts small, a lot of blood vessel destruction can create big problems over time. The retina of the eye is especially at risk, with either sudden or gradual blindness often being the first sign of latent high blood pressure. The kidneys are also a target as it relies on tiny vessels to filter toxins from the bloodstream. Kidney disease causes high blood pressure and also undergoes injury from it.

High blood pressure also increases the risk of blood clot formations. These clots can lodge in an assortment of inopportune locations including the vessels going to the lung as well as the brain.

What Causes High Blood Pressure in Pets?

There are numerous diseases in pets that are associated with high blood pressure:

- Chronic renal (kidney) failure In one study, 93% of dogs with chronic renal failure and 61% of cats with chronic renal failure also had systemic hypertension. More recent studies suggest this may be an over-estimation but the percentages are still significant and patient screening is very important.

- Hyperthyroidism In one study, 87% of cats with untreated hyperthyroidism had systemic hypertension. (Note: hyperthyroidism is a feline disease; dogs are not affected.)

- Glomerular disease is one of the kidney filtration system in which protein is lost in urine. It is important to screen pets with high blood pressure for urinary protein as control of protein loss is important to survival time.

- Cushing’s disease (an adrenal cortisone excess)

- Diabetes mellitus (inability to properly reduce blood sugar)

- Acromegaly (growth hormone excess)

- Polycythemia (an excess in red blood cells)

- Pheochromocytoma (an adrenaline secreting tumor of the adrenal gland)

How is High Blood Pressure Identified?

In veterinary medicine, our patients can’t speak and tell us they’re feeling dizzy or weak. If we’re lucky, based on certain labwork abnormalities such as elevated kidney values, we know to screen for hypertension. Hopefully, it’s caught before it causes issues.In some cases, the cat or dog will exhibit symptoms that indicate high blood pressure may be present.

As a general rule of thumb, If a pet has one of the conditions highlighted above, blood pressure is generally checked. It has recently been recommended that older pets have their blood pressure checked whenever they have a physical examination. And certainly, any pet with a predisposing condition such as one of those listed above should be screened. Ask your veterinarian if your senior pet should get a blood pressure measurement.

The other time high blood pressure is discovered is when it makes its presence known. This usually means some degree of blindness or some other obvious eye problem. The retina of a hypertensive patient develops tortuous-looking retinal blood vessels. Some vessels may even have broken, showing smudges of blood on the retinal surface. Some areas of the retina simply detach. Sometimes the entire retina detaches. With early identification, some vision may be restored.

Do not let minor vision changes go unreported. Let your veterinarian know if you think your pet’s vision is not normal.

Retinal changes can be complicated to interpret. Do not be surprised or alarmed if your veterinarian recommends referral to a veterinary ophthalmologist.

A sudden neurologic condition could indicate a stroke or vascular accident in the brain or spinal cord. It used to be taken for granted that dogs and cats did not throw blood clots and get strokes like human beings can, but the advent of MRI technology has shown otherwise. A sudden neurologic deficit, especially a non-painful one, is another possible indication to screen blood pressure.

Doppler Blood Pressure Monitor

Photo by MarVistaVet

How do we Measure Blood Pressure in Pets?

When a person’s blood pressure is checked, the nurse uses a stethoscope to listen for “Korotkoff sounds” arise and dissipate as an inflatable cuff slowly releases over an artery. In animals, the stethoscope is just not sensitive enough and an ultrasonic probe must be taped or held over the artery. Using ultrasound, the sound of the systolic pressure is converted into an audible signal. It is not possible to measure diastolic pressure in a pet without actually placing a catheter inside an artery so we make do with just a systolic measurement. In pets, this measurement should not exceed 160. A reading of 180 is considered by the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine to indicate high risk for organ damage while readings of 150-159 are considered mildly elevated.

Blood pressure measurement is performed similarly to the way it is in humans. An inflatable cuff is fit snuggly around the foot, foreleg, or even tail of the pet. The cuff is inflated so as to occlude blood flow through the superficial artery. In a person, as the cuff is slowly deflated, a stethoscope is used to listen for the point when the blood pressure is adequate to pump through the partially occluded vessel. This point on the pressure gauge is the systolic blood pressure. The cuff is further deflated until the vessel is open and no more sounds are made. This point represents the diastolic blood pressure and the actual sounds are called “Korotkoff sounds” after the doctor who discovered them.

Some pets (obviously) are nervous at the vet’s office and this factor must be taken into account when reading blood pressure. It is possible for a pet to have high blood pressure at the vet’s office and normal pressure at all other times. You might think this would be a common situation but most pets are able to maintain normal blood pressure despite being surrounded by hospital staff. To account for the “White Coat Effect,” at least five measurements are taken so that the pet becomes accustomed to the process and understands that no pain is involved.

What Treatment is Available for Hypertension?

Ocular disease may require prescription eye drops depending on how much bleeding is in the eye and whether or not return of vision is likely.

When hypertension is identified, a search for the underlying cause is indicated. It may be that controlling the underlying disease totally reverses the hypertension (especially true for hyperthyroid cats).

Beyond these methods, as with people, medication to lower blood pressure is often in order. This typically involves some type of pill that dilates peripheral blood vessels, effectively making them larger so as to accommodate the high pressure blood flow going through them.

Enalapril, an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, is the usual first choice for dogs. It is typically given once or twice daily. Benazepril is another commonly used angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (also called an ACE inhibitor) and might be used in either dogs or cats. When urinary protein loss is felt to be involved, an ACE inhibitor is usually selected as it will lower blood pressure as well as urinary protein loss

Amlodipine, a calcium channel blocker, is often the first choice medication especially for cats. It is much stronger than the ACE inhibitors when it comes to treating hypertension (though it has no direct effect on urinary protein loss). It is typically given once daily. These pills are very small, but a pill cutter can help with more accurate dosing. Alternatively, a compounding pharmacy can create accurately-sized capsules or even a flavored liquid.

Sometimes amlodipine and an ACE inhibitor are combined for a better effect.

Salt restriction in the diet is controversial; it seems to make sense but there is not enough data at present to whole-heartedly recommend it. Certainly, if there is kidney disease present the recommendation is less equivocal as these low salt diets are designed with other features more specifically for kidney disease. This generally means a dry or canned formula prescription diet if the pet will eat it or a diet limited to dry food if the pet will not accept prescription food.