(Also called feline hemotropic mycoplasmosis, infection by Hemobartonella felis, infection by Mycoplasma haemofelis, by Mycoplasma haemominutum, or by Mycoplasma turicensis)

Parasitic organisms survive by attaching themselves to a host and using the host’s body to thrive, generally at the host’s expense. Parasites find themselves protected from the harsh temperature and moisture changes of the external world when they live within the rich, warm body of their host. The parasites this article is concerned with are bacteria that attach themselves to the actual red blood cell membranes of their host, happily riding around, feeding and reproducing until the host’s immune system sees them and begins destroying red blood cells in an attempt to remove them.

Mycoplasma Haemofelis (Formerly Named Hemobartonella felis) and its Smaller Relatives

The term feline infectious anemia has also recently been felt to be inaccurate as there are many infectious organisms that might cause an anemia, which is a lack of red blood cells. For this reason the disease has been re-named feline hemotropic mycoplasmosis, which literally means a blood infection of mycoplasma organisms in cats.

The agent of what has traditionally been called feline infectious anemia is an organism called Mycoplasma haemofelis. This creature is technically a bacterium but is a member of a group of bacteria called mycoplasmas. Mycoplasmas are different from other bacteria because they do not have a cell wall surrounding and protecting their microscopic bodies. They cannot be cultured in the lab like normal bacteria because they must reside inside living cells. This feature not only makes finding them a little tricky but it also limits treatment to antibiotics that can penetrate inside of a hosting cell.

Hemobartonella felis, as it was then called, was first discovered in Africa in 1942 but it was not recognized as a mycoplasma until recently with the advent of gene sequencing. This led to renaming Hemobartonella felis to Mycoplasma haemofelis, though after decades of celebrity under the original name many veterinarians will still refer to it as Hemobart.

Complicating matters further, gene sequencing has revealed two additional species that were previously thought to be variants of Hemobartonella felis. These parasites, which are smaller, have been named Mycoplasma haemominutum and Mycoplasma turicensis. They are much more common than Mycoplasma haemofelis but do not cause as serious an anemia as does M. haemofelis. That said, however, when they are combined with the feline leukemia virus, the former organisms tends to create myeloproliferative disease in the host’s bone marrow while the latter tends to promote the virus’s cancer-inducing abilities. It has been estimated that one cat in 5 is chronically infected with Mycoplasma haemominutum.

What Happens to the Infected Cat?

A cat becomes infected from a bite from an infected flea and soon the cat’s red blood cells are covered with free-loading mycoplasma organisms. The cat’s immune system eventually detects foreign proteins on red blood cells and begins to mount an attack in the form of antibodies. These antibodies bind to the mycoplasma organism as a coating, which serves to mark the infected red blood cell for removal and destruction.

Coated red blood cells are removed from the circulation by the spleen’s natural mechanisms for removing damaged red blood cells. This process breaks apart the infected red blood cell, kills the mycoplasma organism, and recycles the iron for use in new red blood cells.

The problem is that if many red blood cells are parasitized, so many red blood cells are destroyed that the cat becomes anemic.

The infected sick cat is pale, sometimes even jaundiced, and weak. Anemic cats often eat dirt or litter in an attempt to consume iron. An infected cat may have a fever. The initial blood tests show not just red cell loss but a responsive bone marrow (the source of new red blood cells), which means that the cat’s body knows it is losing red cells and is trying to make more as quickly as possible to keep up. Cats with concurrent feline leukemia virus infection tend to have more severe anemia as the virus does not permit the bone marrow to respond.

It can take up to a month after the initial infection before there are enough organisms to make the cat sick. The month following this initial build up is associated with the highest mortality. If the cat recovers, it will become a permanent carrier though stress can re-activate the infection.

How is Diagnosis Confirmed?

Confirming diagnosis has been problematic since the first discovery of the organism in 1942. Because Mycoplasma haemofelis lives inside red blood cells, it cannot simply be cultured in the lab like other bacteria.

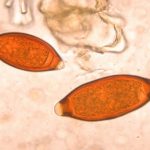

Most reference labs scan all feline blood samples under the microscope looking for the characteristic appearance of infected red blood cells (see graphic at the top of the page).Unfortunately, the number of detectable organisms cycles in a matter of hours such that the number of visibly infected cells can change from 90% to 1% in a matter of 3 hours. This makes it easy to miss infected cells even in a grossly infected cat.

Luckily, all this microscopic scrutiny has been made largely obsolete by PCR technology. PCR testing uses a technique that amplifies small amounts of DNA, allowing of elusive organisms to be detected. Not only can Mycoplasma haemofelis be detected, but also the test can also detect and distinguish the smaller, less harmful mycoplasmas as well. Testing is best done prior to antibiotics, so to allow for best ability to detect parasite DNA. PCR testing is the best test to determine if a cat is suffering from a hemotropic mycoplasma.

Which Cats are at Risk?

The cats at highest risk are those that roam outside in the spring and summer (obviously these cats have the highest risk for flea infestation). Cats that are statistically likely to be infected are male cats younger than 4 to 6 years of age, have a history of cat fights, and have incomplete vaccination histories (in short, cats with somewhat casual care, most likely including casual flea control). Infection with the feline leukemia virus is also a factor in diagnosis. This may be because this immune-suppressive virus allows proliferation of the organism that is not possible in normal hosts or perhaps the anemia associated with the virus directly leads to a sicker cat who is thus more likely to see the vet and have testing. Making matters worse, the mycoplasma seems to enhance the ability of the feline immunodeficiency virus to create bone marrow cancers.

An abnormal immune system is absolutely not a necessity in infection with hemotropic mycoplasmas; normal cats are infected as well. Further, infection with feline immunodeficiency virus does not enhance the severity of hemotropic mycoplasma infection as the leukemia virus does.

Blood sucking parasites such as fleas, ticks, lice, and mosquitoes are the leading candidates for spread of the organism. This makes flea control paramount in protection. Fortunately, there are numerous safe and effective products available to prevent flea infestation.

Cats can become infected by blood transfusion, though animal blood banks routinely screen donors so this is an unlikely route.

Infected mother cats appear to be able to infect their kittens though it is not entirely clear if this is done (renatally, through milk, or by oral contact. Oral transmission from bites is thought to be possible but not confirmed.

Treatment

If hemotropic mycoplasma infection is suspected, initiating treatment is probably a good idea as treatment is much easier than diagnosis. All mycoplasma infections are susceptible to tetracycline. In cats, the derivative doxycycline tends to be most easily dosed as it can be compounded into an oral suspension. Tablets must be used with caution as they can stick in a cat’s esophagus causing irritation and scarring; liquid formulations can be made through a compounding pharmacy. The quinolone class of antibiotics (enrofloxacin, etc.) is also effective against hemotropic mycoplasmas. Three weeks of medication is needed to adequately suppress the organism. Complete clearance of the organism is not generally necessary unless the cat in question is immune-suppressed, FELV-infected, has no spleen, or is to be bred. If complete clearance is sought, sequential use of both doxycycline and a quinolone antibiotic can be used

Killing the mycoplasma is only part of the therapy, however; it is the host’s own immune system that removes the red blood cells and this must be stopped. Prednisone or similar steroid hormone is typically used to suppress this part of the immune system so that the red blood cells are not removed as quickly. Very sick cats will probably require blood transfusions to get through the brunt of the infection. Happily, prognosis is fair if the diagnosis is made in time, as cats generally respond well and quickly to treatment.

Carrier cats are generally not treated. As long as fleas are controlled, a carrier cat is not contagious