Symptoms

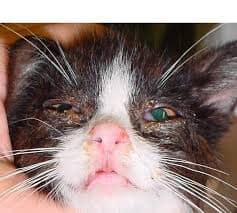

- Sneezing

- Nasal discharge

- Runny eyes

- Cough

- Oral or nasal ulcers

- Sniffles

- Fever

- Hoarse voice

- Or any combination thereof

What Cats are at Risk?

The agents of feline upper respiratory infection are highly contagious and present where ever cats live in groups. Getting infected is easy; a cat simply must socialize with an infected cat or share the same human caretaker, toys or food bowls.

Viruses like herpes, as in people, are forever. So, even if your kitten never sees new cats, he or she is likely harboring the virus from when they were younger. Basically, there is a good chance that any cat or kitten is already infected at the time of adoption or purchase whether or not the cat is showing any symptoms. Kittens are more predisposed due to their immature immune systems, and are usually hit the hardest. When these kittens grow up, they are still infected and symptoms may come out whenever stress suppresses their immune system.

Typically, infected cats come from anywhere there is crowding of close contact with other cats and kittens. Examples are: the shelter, outdoor cats, or cats housed in close contact with lots of other cats (experiencing crowding stress). The average house cat who is not exposed to any rescued kittens, lives with only one or two other cats at most, never goes outside, and leads a non-stressed life is unlikely break with symptoms but may very well be asymptomatically infected.

The chief infectious agents that cause feline upper respiratory infections are herpesvirus and calicivirus, together accounting for about 90 percent of infections. Other agents include: Chlamydophila, Mycoplasma, Bordetella, and others. Of course, a cat or kitten may be infected with more than one agent.

Viruses are spread by the wet sneezes of infected or carrier individuals. The herpesvirus is fragile, surviving only 18 hours outside its host; calicivirus is tougher, lasting up to 30 days. Bleach will readily inactivate either virus but calicivirus is able to withstand unbleached laundry detergents.

Course of Infection

Ninety percent of feline upper respiratory infections are caused by either feline herpes (also called the rhinotracheitis virus) or feline calicivirus. Neither of these infections is transmissible to humans or to other animals.

Most feline colds run a course of 7 to10 days regardless of treatment but it is important to realize that these infections are permanent and that herpesvirus infections are recurring (a property of all types of herpes infections). In kittens, herpes infections are notorious for dragging out. Stresses such as surgery (usually neutering/spaying), boarding, or introduction of a new feline companion commonly induce a fresh herpes upper respiratory episode about a week following the stressful event and the active virus sheds for another couple of weeks.

These episodes may recur for the life of the cat, although as the cat matures, symptoms become less and less severe and ultimately may not be noticeable to the owner. Cats infected with calicivirus may shed virus continuously, not just in times of stress, and may do so for life, although about 50% of infected cats seem to stop shedding virus at some point.

A cat with active herpes symptoms is contagious to other cats for a couple of weeks after a stressful event. Cats infected with calicivirus are contagious for several months after infection but do not appear to have recurrences the same way cats with herpes do.

Most Upper Respiratory infections can be treated by your veterinarian on an out-patient basis. Occasionally, things are more serious. Below are things to raise concern and may require hospitalization

- Loss of appetite

- Congestion with open mouth breathing

- High fever (or the extreme listlessness that implies a high fever if you cannot take the cat’s temperature)

- Noticeable increased respiratory rate and/or effort

If you see the symptoms above or think your cat or kitten is significantly uncomfortable with a cold, you should seek veterinary assistance.

How is this Usually Treated?

How an upper respiratory infection is treated depends on how severe it is and whether or not there seems to be a bacterial infection complicating the viral infection. A mildly symptomatic adult cat might need no treatment at all as the symptoms should naturally wane over one to two weeks.

A heavily congested kitten is likely to need antibiotics and possibly even hospitalization. Antibiotics act not only on bacteria that complicate viral infection but some upper respiratory infections are bacterial and not viral at all.

Besides herpes and calicivirus, the next most common infectious agents are Chlamydophila felis (formerly known as Chlamydia psittaci) and Bordetella bronchiseptica, both organisms being sensitive to the tetracycline family (such as doxycycline). For this reason, when antibiotics are selected, tetracyclines and their relatives are frequently chosen.

Other commonly used antibiotics are: Clavamox®, azithromycin, cephalexin, and clindamycin. Oral medications, and/or eye ointments are commonly prescribed. Severely affected cats may need to have inhalational antibiotics, fluids administered intravenously or under the skin to maintain hydration, and/or some sort of assisted feeding.

Special Therapies

Some cats are severely affected and addressing the secondary bacterial infection is simply not enough to achieve comfort. For these situations, antiviral medications such as famciclovir (same family of drugs as Valtrex) can be used to address the actual viral infection and often even chronic symptoms can be controlled at least temporarily.

Vaccinations

Vaccination is unlikely to be completely preventive for the upper respiratory viruses and is instead meant to minimize the severity of the symptoms. The typival vaccination given to kitten in a series and adult cats annually (or every 3 years depending on the vaccination type) is know as the feline distemper vaccine or called FVRCP – feline viral rhinotracheitis, calcivirus and panleukopenia. The first two provide some coverage against herpes and calcivirus.