What are Coccidia?

Coccidia are single-celled organisms that infect the intestine. They are microscopic parasites detectable on routine fecal tests in the same way that worms are, but coccidia are not worms and are not susceptible to deworming medications. They are also not visible to the naked eye. Coccidia infection causes a watery diarrhea that is sometimes bloody and can be a life-threatening problem to an especially young or small pet. There are many different species of coccidia but for dogs and cats, the most common infections are with coccidia of the genus Isospora. Dogs and cats each have their own coccidia species and cannot infect each other, nor can they infect people.

Where do Coccidia Come from?

Coccidia infection comes from consuming oocysts (pronounced o’o-sists). Oocysts are passed in stool. Once in the outside world, oocysts begin to mature, which means they undergo a process called sporulation, the result being an infective stage. If this stage is consumed by a new host, infection results. The main mechanism of infection is fecal-oral (feces to mouth) transmission.

Alternatively, a host (such as a mouse, fly, cockroach or other insect) can become infected by eating an oocyst only to be in turn consumed by another host (a dog or cat). This would represent another way for a dog or cat to become infected.

Oocysts become infective in only 12-36 hours. Because of this, it is important to remove stool as quickly as possible from the pet’s environment to prevent contamination. Housing animals in groups (especially as might occur in shelters, rescue areas, breeding kennels etc.), leads to more stool exposure which, in turn, increases the risk for coccidia infection. Coccidia are common parasites and infection is not necessarily a sign of poor husbandry.

What Happens after the Host Consumes the Oocyst?

This gets a little complicated but the short version is that the oocyst breaks open and releases eight sporozoites. These eight sporozoites go on to infect intestinal cells where they divide rapidly, eventually developing into a new stage called a merozoite. The merozoites divide and reproduce rapidly, filling up the intestinal cell until it bursts. A multitude of merozoites are released when the cell bursts and they go on to infect and similarly destroy more and more intestinal cells. When enough intestinal cells are destroyed, in three to 11 days, bloody watery diarrhea and disease result.

Merozoites divide and reproduce asexually but eventually a sexual generation of coccidia results in microgamonts, which are male, and macrogamonts that are female. They merge and create an oocyst, which is what started the whole thing in the first place. The oocyst passes in stool where it can infect a new host and the life cycle begins again.

How are Coccidia Detected?

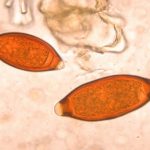

A routine fecal test is a good idea for any new puppy or kitten whether there are signs of diarrhea or not as youngsters are commonly parasitized. This sort of test is also a good idea for any patient with diarrhea and is recommended at least once a year for healthy dogs and cats as a screening test. The above photograph shows coccidia oocysts seen under the microscope in a fecal sample. Coccidia are microscopic and a test such as this is necessary for diagnosis. Small numbers of coccidia can be hard to detect, so just because a fecal sample tests negative, this doesn’t mean the pet isn’t infected. Sometimes several fecal tests are performed, especially in a young pet with a refractory diarrhea (one that won’t go away); parasites may not be evident until later in the course of the condition.

How is Coccidia Treated?

There are two common treatments used for Isospora infections in pets: sulfa drugs (the traditional treatment) and coccidiocidal medications (newer treatment). The most common medicines used against coccidia are called coccidiostats. They inhibit coccidial reproduction. Once the numbers stop expanding, it is easier for the patient’s immune system to catch up and wipe out the infection. This also means, though, that the time it takes to clear the infection depends on how many coccidia organisms there are to start with and how strong the patient’s immune system is. A typical treatment course lasts about a week or two, but it is important to realize that the medication should be given until the diarrhea resolves plus an extra couple of days. Medication should be given for at least five days total. Sometimes courses as long as a month are needed. In dogs and cats, sulfa-based antibiotics are the most commonly used coccidiostats.

There are newer medications that actually kill the coccidia outright: ponazuril and toltrazuril, both actually being farm animal products that can be compounded into concentrations more appropriate for dogs and cats. These medications are able to curtail a coccidial infection in only a few doses and have been used in thousands of shelter puppies and kittens with no adverse effects. Their use is becoming more popular used in kennels, catteries, and animal shelters and you may be pleasantly surprised to find one of them in stock at your regular veterinary office.

Can People or other Pets Become Infected?

While there are species of coccidia that can infect people such as Toxoplasmaand Cryptosporidium, for example, the Isospora species of dogs and cats cannot infect people. Other pets may become infected from exposure to infected fecal matter but it is important to note that this is usually an infection of the young (i.e. the immature immune system tends to let the coccidia infection reach large numbers whereas the mature immune system probably will not.) In most cases, the infected new puppy or kitten does not infect the resident adult animal.