Pneumonia Management in Dogs and Cats

The term pneumonia refers to a serious lung infection. More specifically, it refers to an infection in the deep lung tissues where oxygen exchange occurs and waste gases are removed.

Any time oxygen exchange is impaired, it has the potential to be life-threatening regardless of its cause, and there can be many possible causes. Infectious disease is usually the cause (virus, bacteria, fungus, even a lung worm) but not necessarily.

Pneumonia such as aspiration pneumonia can be caused by inhaling vomited or regurgitated food. Bronchitis is a separate condition from pneumonia, and involves inflamed airways of the lung rather than inflammation in the deep lung tissue itself, but pneumonia and bronchitis commonly go together as the bronhi feed into the lungs and can create an eitiology called bronchopneumonia.

Pneumonia is commonly classified by its original cause:

- Fungal pneumonia

- Viral pneumonia

- Parasitic pneumonia – directly from lungworms or from migration of other worms through the lung.

- Bacterial pneumonia

- Allergic pneumonia – the result of extreme infiltration of the lung by inflammatory cells in the absence of infection.

In most cases of pneumonia there is a bacterial component. This means that no matter what started the pneumonia, bacteria have joined in, adding their nasty effects into the mix as well as worsening the condition, so in most cases, managing the bacteria is vital. This article centers on managing bacterial pneumonia.

When to Suspect Pneumonia

Coughing puppies from the pet store or shelter may have a simple kennel cough but they are high risk for distemper infection, which causes pneumonia.

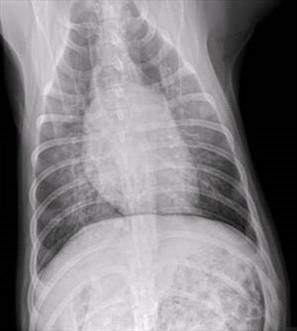

The diagnosis of pneumonia hinges on the chest radiograph (x-ray) but knowing when to take chest radiographs can be tricky.

The veterinarian must put together findings from the history, physical examination, and possibly response to initial therapies to decide if radiographs should be checked.

- Coughing dogs or cats with a fever, listlessness, or appetite loss should definitely be radiographed for pneumonia; though many patients with pneumonia will not have fevers and some will still be deceptively active.

- Coughing dogs with a history of megaesophagus or with a history of symptoms typical of megaesophagus should be radiographed for pneumonia. Megaesophagus involves a floppy, dilated esophagus with a very high risk for regurgitating and aspirating food.

- Kittens with severe upper respiratory infections who do not respond to the usual management should be radiographed for pneumonia.

- Animals with breathing issues should also have radiographs performed

Coughing is often a red flag, but keep in mind not all coughing animals have pneumonia and many pets with pneumonia – especially cats – hardly cough at all.

Bacterial pneumonia does not just happen; it is virtually always caused by something else, so some kind of diagnostics will likely be needed to determine what led to the bacterial pneumonia if it is not readily apparent.

The pneumonia patient may be in one of three states:

- Stable: in other words, eating well and active despite a nasty cough and/or abnormal chest radiographs. These patients can often be treated at home.

- Unstable: poor appetite, inactive, in need of hospitalization.

- Critical: unable to get enough oxygen into their systems and owners note difficulty breathing. These patients require oxygen therapy and 24-hour hospitalization until they can breathe comfortably on their own

The goal is to get the patient stable enough for home treatment as several weeks are needed to fully resolve pneumonia.

If hospitalized, once the patient is eating well, he or she may be discharged with antibiotic pills, a regimen of physical therapy, and a schedule for re-check radiographs (usually weekly).

The hospitalized patient has the following needs.

Intravenous Fluid Therapy

Coughing may be annoying but it is therapeutic and, when it comes to pneumonia, we want to encourage it, not suppress it. Coughing brings up the pus, mucus, and inflammatory cell products that make our patient sick.

If the secretions of the lung are allowed to dry up, the patient will never be able to cough them up. For this reason, IV fluids must be maintained to keep our patient hydrated and keep the respiratory secretions wet.

Antibiotic Therapy

Antibiotics are given to kill the bacteria, but which antibiotics should be chosen? We need something that will penetrate into the pus and mucus, which many antibiotics cannot do.

Often a four-quadrant approach is used that covers bacteria classified as Gram negative and Gram positive as well as those classified as aerobic and anaerobic.

This typically involves two antibiotics used in combination to synergize one another and covers almost every possible bacterial organism.

Alternatively, the lungs may be cultured through a procedure called a tracheal wash. This process involves light sedation, which the patient must be stable enough to withstand.

Sample fluid from deep in the lung is retrieved for culture. A culture identifies the organism and provides a list of antibiotics that can kill it.

If possible, it is best to obtain a culture as a surprising number of resistant bacteria are in the environment and we not only want to confirm our antibiotic choice is appropriate but we do not want to needlessly develop resistant bacteria.

If the patient is sick enough for hospitalization, antibiotics are typically given as injections so as to maximize absorption into the body.

Oxygen Therapy

In most cases, oxygen therapy is not necessary but when a pneumonia patient simply cannot move enough air, oxygen is needed. Room air is 20% oxygen.

An oxygen cage typically is set to deliver 40% oxygen (higher percentages over the long term are actually toxic to lung cells), and oxygen-delivery hoods are also popular. A patient who requires this level of support is extremely sick.

Home Care

Once a good appetite is evident, the patient may be discharged for home care. The following tips are recommended as long as the patient is coughing:

- Do not allow prolonged exposure to extreme cold or wet weather. Keep your pet primarily indoors.

- Consider using a vaporizer (or better yet, buy your own nebulizer, many models are available and are even priced low enough for home use) for 10 to 15 minute intervals a couple of times daily. If you do not have a vaporizer, leave the pet in the bathroom with the shower on to create a misty vapor.

If the bathroom does not get sufficiently misty, a small pet can be confined to a carrier and the vaporizer can be directed into this smaller space. As discussed, nebulization is superior but vaporization is the next best thing.

- Perform coupage at least four times daily and allow light exercise to promote the cough.

- Do not try to suppress the cough with over-the-counter cough suppressants. We want the infected material in the chest to be coughed up.

- Use the antibiotics as directed. Expect several weeks to be required.

- Know when you should return for re-check radiographs.

Pneumonia is a serious infection and several weeks are needed to clear it. Prognosis ultimately depends on what the underlying cause was but the good news is that most patients are not sick enough to require oxygen therapy and the majority of these ultimately recover with proper treatment.