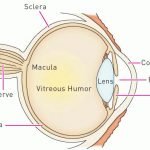

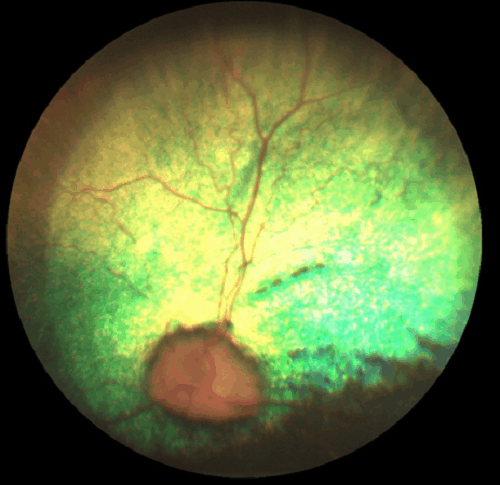

Progressive retinal atrophy, or PRA, describes a group of inherited degenerative disorders of the retina that occur commonly in dogs and rarely in cats. The retina is like the film in a camera. It contains photoreceptors that convert light into electrical nerve signals. These disorders cause the photoreceptors to die prematurely.

The different forms share similar features but have different biochemical causes. PRA has no treatment and no cure but it is not painful.

Both eyes become blind, but the vision loss occurs slowly, giving dogs time to adjust to the changes. Typically the first thing anyone notices is the dog losing the ability to see at night; then over a few months to 1 to 2 years, the ability to see under bright light conditions during the day is also lost. Owners may notice the dog’s reluctance to go outside at night, enter a dark room, or go up or down (especially stairs). The dog may also have dilated pupils as the eye tries to let more light in, and an abnormal shine called tapetal reflection may be seen through the dilated pupils.

Oftentimes the dog adapts so well and the vision changes are so slow that no one notices anything different until the dog is in a new place or when loss of vision is almost complete.

The onset of PRA depends in part on whether the photoreceptors never form properly in the first place (photoreceptor dysplasias) or whether they form properly but then degenerate (photoreceptor degenerative disorders). In the most common type, the photoreceptors develop and function normally at first, but then begin to deteriorate at some point. In the earliest onset form, puppies can have decreased vision by 12 weeks of age and may be blind by 1 to 2 years old. Some degenerative forms begin in early adulthood, some when the dogs are mature, and some as late as 9 to 11 years of age. The type or form differs between breeds of dogs.

PRA is most commonly diagnosed in purebred dogs, but it can be seen in mixed breed animals. Breeds disposed toward the more common degenerative form include the miniature poodle, American and English cocker spaniels, Tibetan terriers, Samoyed, Akita, longhaired and wirehaired dachshunds, Labrador retriever, Papillion, Tibetan spaniel and many more. Breeds disposed toward the less common photoreceptor dysplasia include the Norwegian elkhound, Irish setter, collie, Cardigan Welsh corgi, and miniature schnauzer.

Some dogs with PRA may get secondary cataracts, which are an incidental finding, or they may also be prone to inherited cataracts that make the vision loss happen more quickly. Because of the PRA, no affected dog is a good candidate for surgical removal of the cataracts.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is usually made with an eye examination. Your veterinarian may choose to refer your dog to a veterinary ophthalmologist to confirm the diagnosis, if PRA is suspected. The eye exam involves evaluating the fundus (retina/back of the eye) with specialized lenses. Electroretinography can be used to look at the electrical responses in the retina, and is a good way to confirm PRA if retinal findings are inconclusive. It is usually performed under sedation by a veterinary ophthalmologist.

DNA testing for PRA is available for some breeds; the test can detect if a dog has PRA or is a carrier for it. Affected dogs should not be bred, as that is the only prevention available. See Optigen for further information on which breeds can be tested using the DNA test.

Living with a Blind Dog

Because vision is the third most important sense to the dog (smell is first, hearing is second), most dogs do very well when they are blind. Because PRA develops slowly in most dogs, they have time to memorize their environment, hone the use of their other senses, and adjust to living without vision. They can be so good at doing this that it may be impossible to tell when they finally go completely blind.

Living with a dog who has PRA is not difficult. Your reaction to the loss of vision is likely to be much stronger than the dog’s. These dogs don’t need any medication, their eyes are not painful, and PRA does not affect the rest of the dog as can many other causes of blindness. Keep in mind that it is easiest for them if the furniture isn’t moved and children are taught not to leave toys and clothes out in the dog’s usual pathways. Safety gates, like those used for babies, can help keep them safe from falling down open stairs and preventing other mishaps. Keep the food and water bowls in the same location. Most blind dogs do well outside in their own fenced yards. They can be taught certain commands like “wait,” “curb,” “down,” or “stop” when being walked outside. When you’re travelling, leashes and harnesses are valuable tools.

Sometimes other dogs in the household will serve as seeing eye dogs for their blind companion. The blind dog will follow the sighted dog around and pick up on cues from the other dog.

Be sure to communicate with the blind dog using his other senses, such as smell and sound. Talk to him, avoid startling him when he is asleep by calling him or tapping your foot near him, slap your leg as you walk if you want him to follow you, etc.

As long as you have a good attitude towards your dog’s condition and encourage him to remain an active participant in the family and home, most affected dogs remain happy and otherwise healthy.