What on Earth is the Vestibular Apparatus?

In a nutshell, the vestibular apparatus is the neurological equipment responsible for perceiving your body’s orientation relative to the earth (determining if you are upside down, standing up straight, falling etc.), which inform your eyes and extremities how they should move accordingly.

The vestibular apparatus allows us to walk, even run, on uneven ground without falling, helps us know when we need to right ourselves, and allows our eyes to follow moving objects without becoming dizzy. If you think about it for a minute, it is pretty amazing that any of this is possible so we will take a moment to explain how it works but if you feel you pretty much have the concept, feel free to move on to the next section. The short version is that the vestibular system consists of the structures of the middle ear, the nerves that carry their messages to the brain/central nervous system, and the brain/central nervous system itself.

What’s in the Middle Ear?

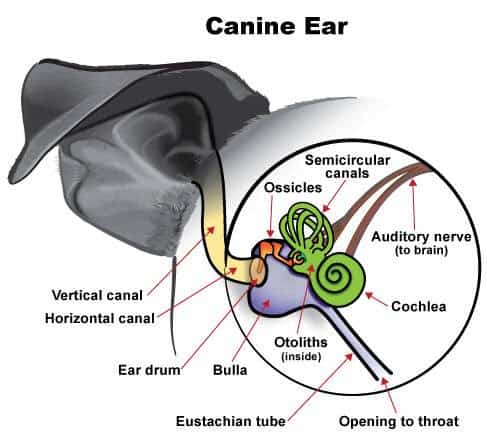

There are two sets of receptors involved: one to detect rotational acceleration (tumbling or turning) and one to detect linear acceleration and gravity (falling and letting us know which direction is up and which is down). Both receptors are located in the middle ear.

Rotation is detected using the three semicircular canals as shown above. These canals contain fluid called endolymph, which moves as the head rotates. Tiny neurological hair cells project into this fluid and are stimulated by the flow. These hair cells are part of sensory nerves that carry the appropriate message to the cerebellum (part of the brain that coordinates walking, running and any other locomotion) and to four vestibular nuclei in the brain stem.

Up and down orientation stems from small weighted bodies called otoliths, which are located within the utricle and saccule of the middle ear. These small otoliths move with gravity within a fluidy gel, stimulating small hair cells as they move similar to the situation described above.

From these centers, instructions are carried by nerve cells to the legs, neck, and eye muscles so that we may orient ourselves immediately. The information about being upside down (or in some other abnormal orientation) is also sent to the hypothalamus (an area of the brain) so that we can become consciously aware of our position. The information is also sent to the reticular formation (another area of the brain – a sort of a volume control on our state of wakefulness. In this way, if we are asleep and start to fall, the vestibular stimulations would wake us up. This is also why rolling an anesthetized animal from side to side is used to hasten anesthetic recovery).

If there is trouble in the vestibular apparatus, then you may not properly perceive your orientation. To put it more simply, you won’t know which way is up, whether or not you are standing up straight or slanted, and you’ll feel dizzy.

The Signs of Vestibular Disease

The following are signs of vestibular disease:

- Ataxia (lack of coordination without weakness or involuntary spasms – in other words, stumbling and staggering around).

- Motion sickness.

- Nystagmus (back and forth or rotational eye movements – The movements will be slower in one direction. This is the side where the neurologic problem is likely to be; however, nystagmus is named according to the direction of the fast component – i.e. the patient may have “left nystagmus” but the problem is probably on the right side of the vestibular apparatus.)

- Trouble with other nerves controlling the head and face.

A Word about “Stroke”

Vestibular signs are commonly (and usually incorrectly) referred to as a stroke. While a vascular accident is a possible cause of vestibular signs, it is a rare cause. Vascular disease, while common in people, is unusual in pets.

Causes of Vestibular Disease

In order to determine prognosis and choose treatment, one needs to figure out what has happened to the vestibular system. The first step is to determine whether the lesion is central – in the brain – or peripheral (in the inner ear).

Idiopathic Disease (Unknown Origin)

Idiopathic vestibular disease is the most common form of vestibular disease in dogs and cats. For unknown reasons, cats are most commonly affected in the northeast U.S. in the late summer and early fall.

Canine idiopathic vestibular disease (also called old dog vestibular disease) and its feline counterpart, feline idiopathic vestibular disease, begin acutely and resolve acutely. Usually improvement is evident in 72 hours and the animal is normal in 7 to 14 days, although occasionally a head tilt will persist. When a case of vestibular disease begins, it may be a good idea to wait a few days to see if improvement occurs before doing diagnostics beyond a routine blood/urine database. These two conditions are idiopathic, meaning we do not know why they occur. We do know that they represent problems in the periphery (nerves of the middle ear rather than in the brain.)

Treatment of idiopathic vestibular disease generally involves control of nausea (motions sickness) while the condition runs its relatively short course.

Brain, the Central Lesion

If the vestibular signs have a central origin, there could be a tumor, vascular accident, infection (especially Rocky Mountain spotted fever) or other lesion in the brain. Imaging of the brain will be important in determining the nature of the lesion and what treatment makes the most sense. This means a CT scan or MRI to image the brain; most likely a referral will be needed for this type of procedure. General anesthesia is required for CT and MRI.There will be some hints in the clinical presentation that the patient in question has a brain lesion causing the vestibular signs. For example, if other cranial nerves are involved and they are on the side opposite from the head tilt, then the lesion is likely to be in the cerebellum (central). If the nystagmus is vertical (the eyes are moving up and down rather than back and forth) or only exists when the animal is placed in certain positions, then the lesion is more likely to be central.

Middle Ear Infection

Middle ear infection is a likely possibility for vestibular disease especially if the patient has a history of ear infections. Concurrent facial nerve paralysis, creating a slackened look to one side of the face, or Horner’s syndrome where there are some eye changes, often go together with middle ear infection.

When an otoscope is used to visualize the external ear of an animal with vestibular disease and debris is seen, this would be a good hint that there is infection in the middle ear as well. However, just because debris is not seen in the external ear does not mean that a middle ear infection is unlikely. Imaging of the middle ear bones may be in order.

The most accessible way to evaluate the middle ear is with a set of radiographs called a bulla series (so named because it focuses on an ear bone called the tympanic bulla). If the bulla appears abnormal, the ear may require surgical drainage. The problem is that radiography is often not sensitive enough to pick up damage in the middle ear and a normal set of films does not rule out disease. In these cases, imaging such as a CT scan or MRI is better, although rather expensive. These imaging techniques, however, allow imaging of the brain tissue itself (which radiology does not), thus allowing brain abnormalities to be evaluated as well.

If the pet has a middle ear infection, a routine cleaning of the external ear can lead to a flare up of vestibular symptoms. This is often unavoidable in long-standing ear infections as there is no simple way to know if an external ear infection extends into the middle ear.

Treating a known middle ear infection can be difficult. Culture of the middle ear may be necessary and oral antibiotics are needed for 6 to 8 weeks to clear the infection from the tiny bones of the middle ear. Surgery may be needed to open the tympanic bullae and flush them out.