When pets have diarrhea that just won’t go away, one test that needs to be run, is the test for Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin.

for Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin.

Clostridium perfringens is a bacterial organism that in an individuals intestinal tract can produce a toxin called an enterotoxin (gut toxin). The situation sounds simple: a pet gets infected with toxin-forming bacteria, gets diarrhea, and the diarrhea should at least improve when toxin-forming bacteria are removed. As with most things, the situation turns out to be more complicated.

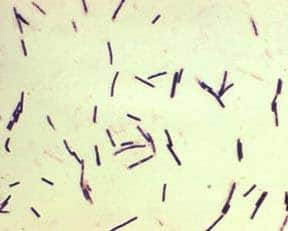

What is Clostridium perfringens?

Clostridial diseases are common in both animal and human medicine. Familiar disease such as tetanus, botulism and the organism that results in gangrene (a dead area of tissue) are all caused by Clostridia species. Clostridia can:

- Pproduce toxins.

- They are anaerobic (they grow in the absence of oxygen).

- They form spores (essentially armor) so as to withstand environmental change, including disinfectants that would kill more vulnerable bacteria.

Clostridium perfringens is one of the species of the Clostridium family but is further classified into five types depending on what combination of four enterotoxins it produces.

While these toxins can be seen in normal dogs, in high amounts, they are associated with diarrhea.

How Would Clostridium perfringens Infection Happen?

The organism could be consumed in food. When it arrives in the small intestine, it forms a spore (sporulates) and begins to produce its toxin. Alternatively, the organism may have been happily and innocuously living in the intestine for who knows how long when something causes it to sporulate and produce toxin. The trigger may be dietary, may be related to infection with another organism, or may even related to giving a medication. The type of diarrhea produced by the toxin is generally a colitis, meaning the large intestine is affected. Such types of diarrhea are mucous, possibly bloody, and associated with straining. A more watery diarrhea, as comes from the small intestine, is also possible. Severity of the diarrhea can range from mild to life-threatening depending on how much toxin is produced.

The important concept is that Clostridium perfringens toxin can be the cause of the chronic diarrhea or it can be a complicating factor in a diarrhea caused by something else.

Can We Test For Toxin-Producing Strains Of Clostridium perfringens?

In the past, looking under the microscope for clostridial spores was thought to be helpful, since we know the organism must change to its spore-form to produce toxin. Apparently, the organism sporulates without necessarily producing toxin so this method has not been as helpful as we had hoped.

This is the crux of the problem. can be cultured from the feces of 80% of dogs whether they have diarrhea or not. Plus, we know that while C. perfringens enterotoxin certainly causes diarrhea, some dogs seem to be unaffected. Clostridium perfringens can be cultured from the feces of 80% of dogs whether they have diarrhea or not. The culture will not tell us if the strain present can produce the enterotoxin. Clearly we need to know more than whether there is any Clostridium perfringens. This is where PCR testing comes in; it is a form of DNA testing whereby the Clostridium perfringens are tested for the DNA needed to make the different enterotoxins. In this way, we can detect the genes that are specifically capable of producing enterotoxin. Furthermore, the number of gene copies can be measured so that we can tell if there are large or small amounts of toxin genes. Large amounts of toxin genes are associated with disease, so that in this way we can tell if one of the Clostridium perfringens enterotoxins is likely to be contributing to the patient’s diarrhea.

Severity of the diarrhea can be mild all the way to life-threatening.

When Should We Treat For Clostridium perfringens?

Let’s begin with the obvious: a dog does not need to be treated for Clostridium perfringens unless he has diarrhea. Since 80 percent of dogs harbor Clostridium perfringens whether they have diarrhea or not, culturing Clostridium perfringens from a fecal sample will not be adequate for diagnosis; we have to find the toxin or, at the very least, verify significant amounts of Clostridial genes capable of producing toxin.

Getting back to the dog or cat with chronic diarrhea, the chances are that a fecal check for worms has been done and a trial course of an anti-diarrheal medication has been done. A possible next step would be a PCR panel that detects the DNA from an assortment of viruses and bacteria associated with diarrhea. Often this type of panel includes a test for Clostridial enterotoxin DNA. The laboratory will report a quantification of gene copies for CPA (the gene for the alpha toxin), CPE (the gene for the epsilon toxin), and CP net E/F (the gene for the net E/F toxin). If the number of toxin genes for any of these toxins is significant, treating with antibiotics against Clostridium is indicated.

Keep in mind that clostridial diarrhea might be the entire problem and curative with the right antibiotic or it might be secondary to a bigger problem yet to be discovered.