What Is The Trachea Anyway?

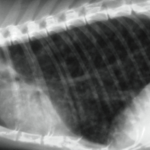

Trachea is the scientific name for the windpipe, the tube that connects the nose, mouth, and throat to the lungs. The trachea is meant to be a fairly rigid tube. It consists of muscle connecting a group of cartilage rings. The rings are actually not complete circles; they form a C with the open end of the C facing towards the animal’s back. This muscle covering the open end of the C shape is called the tracheal membrane or sometimes the trachealis muscle.

When the diaphragm (the flat muscle separating the abdomen from the chest cavity) flattens and the intercostal muscles (the muscles between the ribs) move, air is sucked into the lung. When the muscles move the opposite direction, air is pushed out of the lung. The trachea serves as a pipeline bringing air into the chest. Part of the trachea is in the throat but it also extends into the chest so that we can look at the trachea as having an intrathoracic portion (inside the chest) and an extrathoracic portion (outside the chest).

Why Would A Trachea Collapse?

Tracheas collapse because the cartilage rings weaken, which is where the term tracheomalacia comes into play. Tracheomalacia is the condition where the cartilage becomes spongy and soft. Cartilage in this condition cannot hold its rigid C-shaped supportive structure. When the C-shape loses its curvature, the tracheal membrane across the top stretches out and loosens, becoming floppy. Instead of being a tight muscle canopy, the now flimsy membrane moves as air passes through the trachea. When air rushes into the chest, the membrane of the intrathoracic trachea balloons outward, and when air rushes out the membrane of the intrathoracic trachea droops down into the C cartilage and causes an occlusion. The tickling sensation of the membrane touching the tracheal lining generates coughing, and if the obstruction interrupts breathing the patient may become distressed. If the collapse is in the extrathoracic (also called the cervical) trachea, the opposite occurs: the collapse occurs during inhalation and the ballooning during exhalation. In the unluckiest of patients, the tracheomalacia extends down the bronchi (large airways that feed each lung). These patients have the worst prognosis and the worst coughing.

Panting or rapid breathing for any reason makes the collapse and anxiety worse, which unfortunately tends to generate more rapid breathing and a vicious cycle of distress.

Making things worse still is the inflammation generated in the trachea. The collapse creates increased secretion and inflammation, thus promoting yet more coughing, which creates yet more inflammation. The enzymes involved in inflammation further soften the tracheal cartilage, making the collapse worse.

Ultimately, the tissue of the trachea changes and loses its normal characteristics and the condition gets worse and worse.

The trachea may be collapsed along its entire length, only in the intrathoracic section, or only in the extrathoracic section. Most commonly the collapse is at its worst right where the trachea enters the chest.

What Animals Are Affected?

The victim is almost always a toy breed dog, with poodles, Yorkshire terriers, and Pomeranians most commonly affected. The disease usually becomes problematic in middle age but can occur at any age. The cartilage defect that leads to the flattened C rings seems to be hereditary.

Many dogs with collapsed tracheas do not show symptoms, however, until a second problem complicates matters. Factors that bring out symptoms might include:

- Obesity

- Anesthesia involving the placement of an endotracheal tube

- Development of kennel cough or other respiratory infection

- Increased respiratory irritants in the air (cigarette smoke, dust, etc.)

- Heart enlargement (the heart can get so big that it presses on the trachea)

- If a secondary factor such as one of those listed above should occur and make a previously incidental collapsed trachea problematic, oftentimes removal of the secondary factor (weight loss program, getting an air filter, etc.) may clear up the symptoms of the collapsed trachea.

Treatment

The following steps are often helpful in long-term management of the tracheal collapse patient:

- If any of the above listed secondary problems are of concern, they must be addressed. This may mean that the owner gives up cigarettes or that the dog goes on a formal weight loss program or other treatment to resolve the exacerbating problem.

- Dogs with collapsed tracheas become unable to efficiently clear infectious organisms from their lower respiratory tracts. Antibiotics may be needed periodically to clear up infection.

- Cough suppressants such as hydrocodone, butorphanol, or tramadol may be handy.

- Corticosteroids such as prednisone and related hormones cut secretion of mucus effectively but are best used on a short-term basis only due to side-effects potential. Long-term use may promote infection and weaken cartilage further. Inhalers for dogs, similar to what asthmatic humans use, may be helpful in delivering corticosteroids while minimizing side effects.

- Airway dilators such as theophylline or terbutaline are controversial as they may dilate lower airways but not the actual trachea. By dilating lower airways, however, the pressure in the chest during inhalation is not as great and the trachea may not collapse as greatly.

In a recent retrospective study of 100 dogs with collapsing trachea, 71 percent responded to medication and management of secondary factors (obesity, irritants in the air, etc.), 7% had disease so severe that they died within one month of diagnosis, 6 percent had severe additional disease problems, and the other 16 percent were felt to be candidates for surgical treatment (see below).

Emergency

The patient’s distress can reach a level so severe that the normally pink mucous membranes become bluish and collapse can result. When this occurs, tranquilization is helpful to relieve the anxiety that perpetuates the heavy breathing and coughing. Oxygen therapy and cough suppressants also help. If the patient reaches the point where distress seems extreme or if collapse results, treat this as an emergency and rush the pet to emergency veterinary care.

Surgery?

If medical management does not produce satisfactory results, it is possible that surgery may be beneficial. There are two procedures currently in use: placing steel tracheal rings to shore up the weakened cartilage, and placing a cylindrical mesh prosthesis referred to as a tracheal stent. Either one might be used though in recent years there has been a trend towards the mesh stent and away from the ring prostheses. Both procedures have potential for complications and while improvement can be expected, patients will still require oral medications for coughing at least some of the time.

Surgical solutions for tracheal collapse are not for mild cases; they are for cases that cannot be adequately controlled by medication, weight loss, and other non-surgical means. If you are interested in pursuing a surgical solution, speak to your veterinarian about what is involved for your particular pet.

Surgery for a tracheal collapse may be a procedure that your veterinarian is not comfortable performing. Discuss with your veterinarian whether a referral to a specialist may be in your pet’s best interest.

Is Liver Disease Associated?

In the July/August 2006 issue of the Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, a group of researchers led by Natali B. Bauer pursued the common finding of enlarged liver in dogs with tracheal collapse. Her group looked at 26 dogs with tracheal collapse and compared liver function test results to 42 dogs without tracheal collapse. Ninety-two percent (92 percent) of dogs with tracheal collapse were found to have abnormal results. Dogs that received stent placement to assist their breathing showed improvement in these tests. It was concluded that oxygen deprivation from the collapse had resulted in significant liver disease in many tracheal collapse patients. It was further recommended that tracheal collapse patients have liver function tests periodically performed as liver supportive medications may be helpful.